By Samuel Peckett

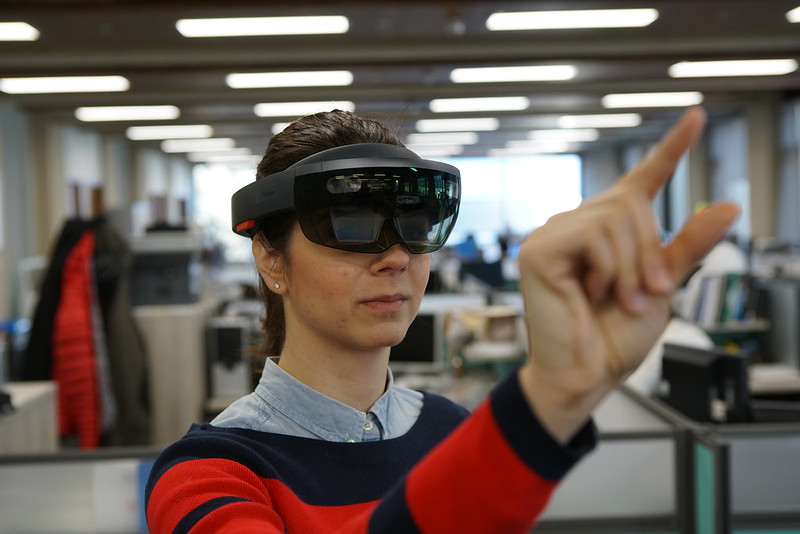

Immersive journalism’s wow factor is easy to understand. Being able to look around in 360-degree photos and 360-videos using your phone is impressive. So, too, is using virtual reality (VR) headsets to be taken to places you’ve never visited before, or using augmented reality (AR) to superimpose images onto the real world through your smartphone’s camera.

The wow factor with immersive technologies has been well documented, including in journalism. While this is exciting for the medium and helps bring new people to the technology, Alisdair Swenson, Research Associate at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Creative AR and VR Hub, says it likely won’t last forever.

“The risk with VR is that the first time you use it, it’s really cool, and maybe again a few times after that – there’s a real novelty. People just want to try VR. That’s going to disappear quite quickly as more people try it and get used to it. Using a VR headset itself isn’t going to be the draw, it’s going to be having a compelling experience.”

Phil Birchinall, Senior Director for Immersive Content at Discovery Education, a company that utilises VR and AR in the classroom, says that you need to be careful not to rely on this wow factor.

“We’ve got to be careful with immersive technologies and treat it like a laser, pointing it exactly where you need it rather than just doing it for the sake of it. It still has a wow moment – if done right. If you’re teaching children about Mars and the planet just appears as a globe in front of them, they’ll just go: ‘So what?’

“‘So what?’ is one of our principle questions – if you’re just doing it for the sake of doing it there’s no point.”

You now need to make sure you’re creating a compelling experience, and a way to do so with immersive journalism is utilising its ability to create empathy in the story you’re telling.

The ’empathy machine’

Alisdair said: “VR allows you to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. This idea of embodiment and inhabiting a character and what that means for you psychologically leads to what we call the ‘empathy machine’. That level of empathy and embodiment is very strong in VR.”

Nonny de la Peña, regularly referred to as the ‘Godmother of Virtual Reality’ and oft credited with helping to create the genre of immersive journalism, also calls VR an ’empathy machine’ due to it’s ability to allow you to interact with people and places you wouldn’t usually be able to, helping you to understand them better.

Dr David Dunkley Gyimah, Senior Lecturer in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University, explained a breakthrough moment for documentary film also utilised emotional impact.

“The breakthrough movie was a film called Primary, which was about Kennedy going for the presidency and there’s a major scene in that film when the cameraman follows Kennedy onto the stage, while every single other news crew was stuck to a tripod. You go all the way onto the stage. For the first time, you’re in the emotion.”

Immersive technologies allow us to now go one step further. In this example, instead of simply joining Kennedy as he walks on stage, you could now experience these emotions by ’embodiment’, walking onto the stage as Kennedy through VR or 360-degree video.

David added: “VR builds on immersion in ways only technology can. It’s a heightened sense of the world.”

Stories told through immersive technologies stick with those who experience them longer than text-based stories, too. In an article for the Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking journal, it was explained that consuming a story via immersive technology increases the consumer’s sense of a story’s credibility, their story recall and their story-sharing intention, as well as their feelings of empathy.

As a result, telling stories through immersive journalism can help create a more complete picture. Not only does the consumer understand what happened, they also have a better idea of how the people who experienced it felt through increased feelings of empathy. That’s a huge feature for immersive journalism as the wow factor begins to wane.

As Alisdair said: “A picture speaks a thousand words, but if we can put someone in an immersive or 360-degree environment, then how many words is that?”